Three disparate and difficult challenges threatened to defeat the Continental Army and its commander in the long winter at Valley Forge. The British from without, betrayal and bereavement from within.

For two and a half years, General Washington had mounted a dogged resistance to the global imperial power. In the fall of 1776, at the Battle of Brooklyn, 20,000 British soldiers began to encircle the Continental Army. The Royal Navy patrolled New York’s waterways, blocking escape. Providential fog hid small boats that carried 9500 American soldiers and the ember of the revolution to Manhattan. Pushing off the shore of Long Island, in the last boat was, George Washington.

Sorely in need of a victory, he devised a bold plan. Failure meant certain death, but success might turn the tide of war. Washington and 2400 troops navigated treacherous ice filled waters at night. Then marched four hours through sleet and snow to surprise the British at Trenton. Washington had crossed the Delaware on Christmas night to win the first major victory of the war. Victory at the Battle of Princeton soon followed.

That summer, Washington’s forces fought two major battles, narrowly losing both, but proving that they were a force to be reckoned with. Washington’s troops entered Valley Forge, as one observer quipped, “disappointed but not defeated.”

Through the extended winter, Washington waged war on three foes. The Conway Cabal sought to remove him as Commander in Chief. The privation in the camp, which Washington described in February as, “this fatal crisis.” And finally, there was the issue of the British. They outnumbered Washington’s troops and held the city of Philadelphia, from which Congress had fled. An armada of 400 vessels sailed up and down the coast, supporting and supplying British regulars.

But Washington was an inveterate campaigner that understood the British, in part, because he had been trained by them.

In the winter of 1753, he was a Commissioned Major for one of Virginia’s militia districts. He made a seventy-seven day journey in inclement weather, over rough terrain, through the Ohio Valley as an emissary to the French at Fort LeBoeuf. His report detailing the arduous journey was published in London and Virginia, obtaining him a measure of distinction.

The next year, Virginia Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Washington led an attack that started a world wide war. He was establishing a defensive position in the woods of present day Pennsylvania when he was informed that a party of fifty French soldiers where hiding nearby. He led a group of forty militia and allied natives to rout them. The successful attack began the opening salvoes of the French and Indian War and led to the Seven Years’ War.

In 1755, Washington volunteered as an aide-de-camp to General Braddock. Braddock's forces were ambushed by the French, his officers were killed, and he was mortally wounded. Washington was the only one left to relay the general’s orders to the men. He had two horses shot out from under him and four bullet holes were found in his coat. Though it was a resounding defeat for Braddock, Washington was hailed as, “the hero of the Mononghela.” It was later revealed that he was also suffering at the time from the bloody flux, i.e., dysentery, making his physical exploits that much more impressive.

Washington was promoted to Colonel and Commander in Chief of all Virginian forces and was lauded for his bravery on both sides of the Atlantic.

Not having the aristocratic blood to secure a higher position in the British army, nor possessing the wealth to purchase one, Washington resigned his commission in 1758. He returned to Mount Vernon to become a farmer, husband, and step-father. He served Virginia in the House of Burgesses for sixteen years until the Revolutionary War.

At Valley Forge, Washington readily deployed the skills he had honed as an elected representative in the political knife fight that was the Conway Cabal.

Quarter Master General, Thomas Mifflin, and Brigadier General Thomas Conway conspired with a handful of politicians to replace Washington as commander of the Continental Army with General Horatio Gates. Gates, who had won a lopsided victory over the British at the Battle of Saratoga, was amicable to the coup d'état.

When Washington was made aware of communique critical of him, he sensed something more was amiss and responded swiftly. He called upon Conway to explain why he had denigrated him in a private letter to Gates, forcing Conway into a catch-22.

Mifflin and Gates secured positions on the Board of War, seeking to weaponize its obscure oversight function to compel Washington bureaucratically. When Gates arrived at Valley Forge, Washington treated him with deference, but denied him access to the army, stating that while Congress had appointed Gates they had failed to supply him with written orders.

The Board of War pivoted and proposed an invasion of Canada, thinking that a northern victory would indurate their power. Washington publicly deferred to their expertise, while privately acknowledging the folly of the scheme. Having parried the first thrust, he turned his attention to the conditions at Valley Forge.

No issue was too small for George Washington’s attention as he made his daily rides through camp. He oversaw the removal of waste and placement of hospitals.

About one third of the force were unfit for duty due to lack of clothes or shoes. Officers fashioned coats out of blankets and soldiers stripped clothes off the dead. Washington installed cobblers and redesigned the uniforms to use less fabric. He slept in a tent until housing was built for all the soldiers.

At night, after a meager supper, he conducted his correspondence and prevailed upon members of Congress to visit the camp. Congress and the Continental Army were the only two institutions that had been created by the young country.

A congressional delegation arrived and was appalled at the depredation. They witnessed soldiers leaving bloody trails in the snow from their shoeless feet. Weather made the roads impassable and seized up the army’s supply chain. Leaving the men without meat for days.

The delegation also witnessed how the general comported himself with regal presence and noted the gravitas his men bestowed upon him. Within six weeks, the delegation remedied supply and other issues Washington had detailed in a 13,000 word report written by his aid, Alexander Hamilton.

Washington deftly used the stone of the delegation to kill two birds, firming up congressional support and uncovering the corruption and negligence of Quarter Master General, Mifflin, whose duty it had been to properly supply the troops.

The northern offensive that Mifflin and Gates were planning proved futile and was abandoned. After Congress demanded to see Conway’s correspondence to Gates critical of Washington, both Conway and Mifflin resigned from the army. Gates was demoted to a quiet post. Washington’s swift direct response, followed by seasoned patience and shrewd political maneuvering, defeated the enemies within. Help defeating the enemy without came from an unlikely source.

Congress gave an appointment at Valley Forge to a Prussian military officer after he was introduced to them by Benjamin Franklin. Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben wore big pistols with decorative holsters, his grasp of English did not extend beyond profanity, and he had an Italian greyhound that followed him everywhere and howled at off-key singing.

His eccentricities and enthusiasm built immediate rapport with the soldiers, whom he set about training using pantomime and interpreters. When Washington noted Baron von Steuben’s precision and methodicalness, he ordered all troops to be trained in the same manner. Hitherto, dissimilar practices had been used by militia and regulars as well as different commands.

Within three months, Baron von Steuben taught the army how to march in columns instead of lines, how to turn, and move in formation.

Muskets are not accurate and take time to reload. Their effectiveness comes from shooting in volleys. Baron Von Steuben instilled trigger discipline in the Continentals, teaching them to hold fire and to fire in volleys. He simplified and regularized commands, which Washington ordered universally adopted.

Washington used the brutal winter to quash a cabal, solidify support, and enhance the army.

After the snow melted, the Americans secured an alliance with France. For the first time in the war, the Continentals had an answer to British sea power, the French Navy.

The wisdom of Washington’s offensive posture throughout the winter, that many had decried for sapping resources, was proved true. The British abandoned Philadelphia to reenforce New York and Washington was well positioned to pursue them and win a substantive victory.

General Washington used the Valley Forge of circumstance to refashion his army, fixing its supply chain and standardizing commands and training. Those improvements allowed him to lead the Continentals through five more years of war to victory, securing the cause of independence and liberty for posterity. It also ensured that he would later be eulogized as, “First in war.”

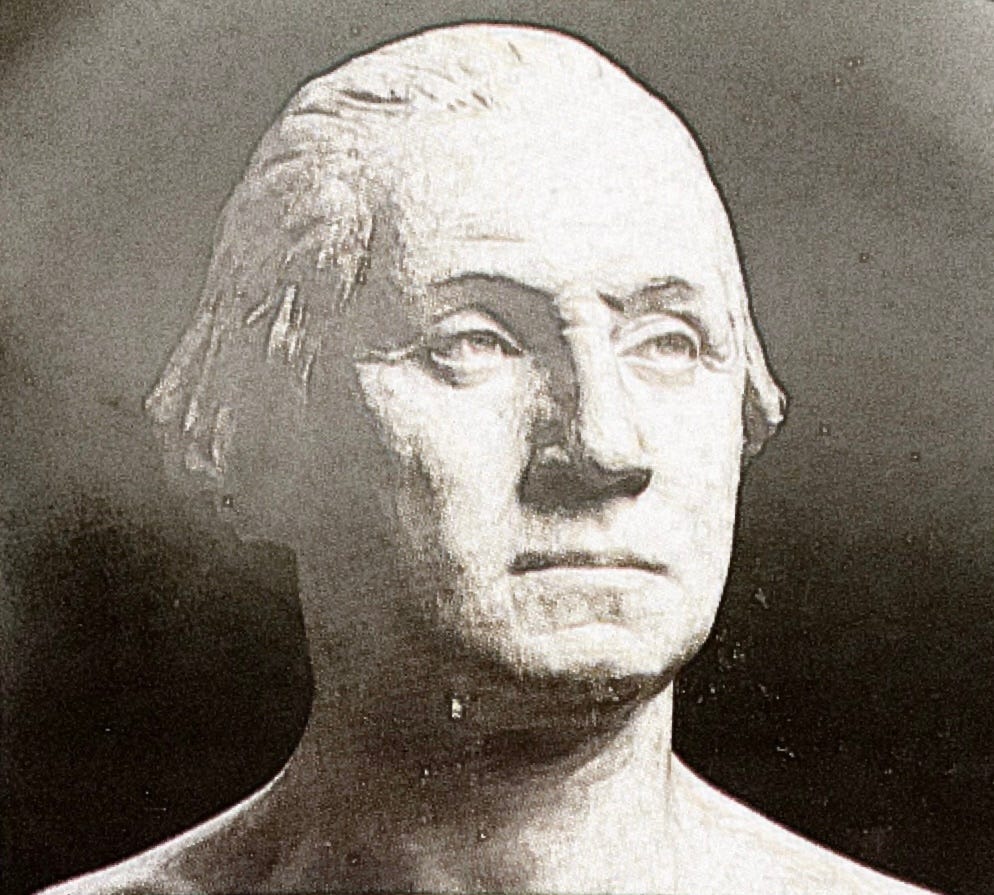

Terra cotta bust of George Washington created by Jean-Antoine Houdon. Image taken of ticket stub from Mount Vernon, 16 MAR 2022.

Sources: George Washington: The Political Rise of America’s Founding Father by David O. Stewart; displays at Mount Vernon & Mount Vernon’s website.

Share this post